By Alex Rosenblum / Special to the BJV

My son-in-law AJ Reisman – amateur chef, prolific blogger, published children’s author, and product manager at a startup Arbor focused on bringing families together through shared history – sent me a text message with a recent article from The New Yorker titled, “Recipes from the Survivors of Auschwitz,” by Hannah Goldfield. The introductory blurb read: “Survivors of the Holocaust meet up to launch a cookbook — recipes for matzo-ball soup, kogel mogel, and Marion Wiesel’s onionless latkes, favored by her husband, Elie.”

“What do you think?” wrote AJ.

“Nu, what do I think?” – I asked myself this question over and over again, without reading past the introduction. “Recipes from the Holocaust” simply did not make sense to me. In my ignorance of the contents of the article, I was annoyed and perhaps even angry. To put Auschwitz and recipe in the same sentence was the perfect oxymoron – a hurtful, incongruous use of words.

And so, in response to my son-in-law’s inquiry, I, a son of an Auschwitz survivor, sat down to memorialize my thoughts and answer him. By coincidence, at the very same time AJ prepared his daily blog with The New Yorker article as his central theme. Fully prepared after reading and digesting the article, AJ, a fourth generation American, pointed out to his readers:

“Food is how we remember families, honor tradition, and understand stories.”

“From the story of Exodus, ’That night, they are to eat the meat, roasted on the fire; they are to use it with matzo and marror.’”

“It’s through recipes that we can remember and understand kin. Even if we do not know our ancestors, we taste a flavor of their life. And when you break bread with a family recipe, stories get shared, and you never forget history.”

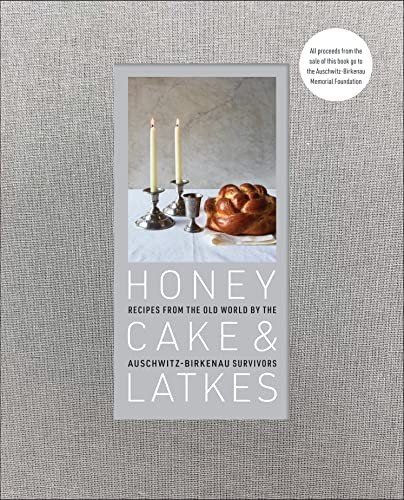

Only later did I bother to read Hannah Goldfield’s wonderful account of the Auschwitz survivors who celebrated the recent publication of the cookbook, Honey Cake and Latkes: Recipes from the Old World by the Auschwitz-Birkenau Survivors, at the Neue Museum in New York. (The museum’s patron, Ronald Lauder, is also chair of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial Foundation, which organized the publication of the book.) The survivors described how the excruciating pain of cruel days and nights in the death camp was slightly alleviated by the inmates’ conversations about the food from the pre-war days in the haym (pre-war home) that they so dearly missed and longed for. In their own small way, these memories kept many alive.

Not surprisingly, I was tainted by my own inability to fully relate to my own father, Yidl Moishe Rosenblum’s, survival of Auschwitz. Auschwitz was not a topic often discussed in der haym (our house). My two younger brothers and I culled secondhand information about der khurbn (holocaust) in Auschwitz from our mother, who had managed to survive Bergen-Belsen. Occasionally, we would overhear the few surviving landsleit (friends from the same town) who would get together and, over a glayzeleh bronfn (glass of whiskey), quietly and somberly talk about the lahger (concentration camp) days – to me, half-understood stories of pain, horror, starvation, and mazel in surviving.

I turned to my wonderful wife of fifty years, Sabina, and told her about The New Yorker article my son-in-law forwarded to me and my initial reaction to it. Sabina was the rikhtike yankee – the real American – in our family, born in Brooklyn with parents born in Manhattan. Her Bubbie Sadie and Zeydeh Louie Laybish arrived in Ellis Island from the Pale of Russia circa 1905. In the late 1960s, all three generations lived in an extended family setting in Bensonhurst, which is where I courted my wife. And Zeydeh Louie was my winning connection. No other suitor could get past Zeydeh Louie in his rocking chair near the home entrance. Once I was able to engage him with discussions of pogroms, the voyage to America, and living on the Lower East Side – all in my tzehbrokheneh (broken), but passable, Yiddish – I became his choice as the boyfriend with the best khosen (groom) potential.

Upon our marriage, Sabina became a real ballehbosteh, working full time as teacher, managing our house in Brooklyn and the weekend home in the Berkshires, and raising our two daughters. Early on, she decided that it was time to show the in-laws her own American-style cooking prowess. She prepared a sumptuous vegetarian meal with pastas and numerous vegetables and soup. After the meal, she turned triumphantly to my father and inquired as to his reaction to this grand vegetarian meal. My father smiled, nodded, and declared to the family, “zayer git – very good!” As my wife walked toward the kitchen with the tray of empty dishes, my father turned and whispered into my ear, “Takeh, zayer git…ober, vos hot geshen tzu a shtikl flaysh un broyt?” (“Really, very good – but what happened to a piece of meat and bread?”)

Only years later did I tell my wife what my father had said to me that day in confidence. I simply could not explain with any comfort and certainty why bread was important to him. What remains to this day is some form of a legacy and memory of ‘Auschwitz and food’ based on the passive participation of my brothers and me in an unusual ritual at our family’s Friday night Shabbos meals. We listened and watched without understanding, and I’m not sure I understand even today.

The Shabbos lights were lit, the wine was poured, and the khallah was torn apart and passed around. My father would pause and stand up while holding a small piece of khallah, then show it to us and say, “Vos ikh volt gehkent teayen in lahger mitt dos shtikl broyt!” – “What I could have done in the concentration camp with this little piece of bread!”

Ramblings from me, a child of survivors and an old man now, or an important lesson for dee ayniklekh (the grandchildren) from their father and their grandfather, saved and passed on for posterity?

Alex Ziske Rosenblum is an attorney and the Berkshire Jewish Voice’s bronfin (whisky) correspondent, whose last article for this paper was the second installment of his history of Jews and alcoholic beverages. He has a home in Richmond.